From crimethinc.com

A History of Anarchist Counter-Inaugural Protest

Thousands of protestors will stream into the streets of Washington, DC on January 20 to oppose the incoming presidency of Donald Trump. As they march, chant, unfurl their banners, and attempt to disrupt the inauguration, they step into a decades-long history of protests against the presidential spectacle.

What follows is a history of anarchist counter-inaugural activity from its first stirrings in 1969 to the high point of the anti-globalization movement in the early 2000s, through the failures of the Obama years to today. As we plan our resistance to the Trump regime and the world that makes him possible, let’s consider the successes achieved and the limitations encountered by previous anti-authoritarian generations. We have much to learn from the Yippies, flag burners, radio pirates, and black blocs that preceded us. What we do with their legacy is up to us.

For more information about the upcoming 2017 counter-inaugural protests, see the “No Peaceful Transition” call for militant anarchist action against Trump, and the Disrupt J20 page from the DC Counter-Inaugural Welcoming Committee.

The First Counter-Inaugural Protests: The Nixon Era and the Decline of Radicalism

Protestors, anarchist and otherwise, have confronted presidential inaugurations for many years. The earliest known disturbance took place in 1853, when a group of unemployed men attempted to stage a protest at the inauguration of Franklin Pierce, but were easily repelled by police. From that point on, however, no documented protests took place until the heyday of the civil rights, countercultural, and anti-war movements of the late 1960s. In this heady environment of revolutionary militancy, radicals achieved the confidence to disrupt the inauguration spectacle for the first time.

The first major counter-inaugural protest took place in 1969, when Richard Nixon was elected on the heels of the chaotic Democratic National Convention protests in Chicago and massive mobilizations against the war in Vietnam. In this atmosphere of rebellion, the inauguration presented a natural target for resistance. However, at a December 1968 convention of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), delegates rejected a proposal for a protest at Nixon’s inauguration. Speakers from the organization’s Black caucus argued that it would not be in the interest of the Black community, asking delegates to consider “whose heads are going to be busted.” Despite this dissension, a variety of New Left and peace groups took to the streets to articulate opposition to the incoming regime. While most framed their activity through the dominant rhetoric of nonviolence, others proved uncontrollable.

According to the New York Times, “A small, hard core of the country’s disaffected youth hurled sticks, stones, bottles, cans, obscenities, and a ball of tin foil at President Nixon” and his entourage during the inaugural parade. As Nixon’s motorcade approached, the protestors threw firecrackers and smoke and paint bombs, forcing the President’s car to speed away. After police drove them back from the parade route, the 300-400 “ultramilitants” raged through five city blocks, smashing the windows of banks, businesses, and police cruisers, writing graffiti, chucking bottles and stones at police and soldiers, and repeatedly burning the small American flags handed out by Boy Scouts along the parade route. Lest their politics be confused for those of the liberal anti-war organizers, they marched with “a mottled black bag that they said was supposed to represent ‘the black flag of anarchy.’” Eighty-one rioters were arrested. The rebellious young people were condemned by the nonviolent organizers whose limits they surpassed—a dynamic that remains familiar to this day.

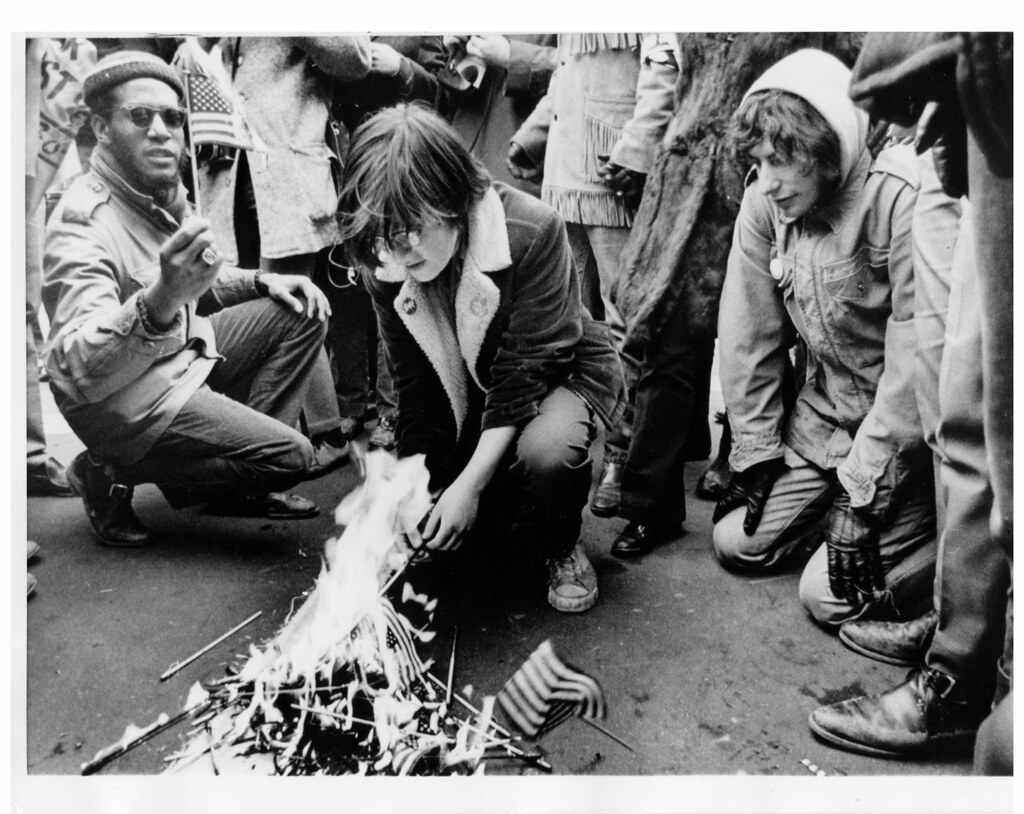

Nixon’s second inauguration in 1973 saw larger but tamer protests. A massive crowd thronged the capitol grounds—from 60,000 to 100,000 strong according to various estimates—and a large march organized by prominent left and activist groups took place. The peace police were out in force, with speakers urging the crowd to remain orderly and marshals along the march route preventing disruptions. A radical march including SDS, the Progressive Labor Party, and “uninvited but active contingents of Yippies” aimed to get within audio range of the inauguration ceremony to disrupt it with noise. However, police successfully delayed the demonstration’s arrival until the ceremony had already concluded. Young people removed and burned the flags around the Washington Monument, replacing them with Viet Cong and other flags, while a few stone throwers managed to cause some minor ruckus around the inaugural parade route. Thirty-three arrests were reported.

The internal pacification within the protests foreshadowed the continuing decline of radical movements. As the corporate media drily noted, the protestors, scolded into passivity, quickly got bored with the litany of speakers in a familiar top-down format: “The cold weather and the familiarity of the rhetoric combined to disperse most of the protestors within little more than an hour.” A similar trajectory would emerge when the riotous diversity of the anti-globalization movement gave way to the larger but monotonous and top-down marches of the anti-war movement in the early 2000s.

By 1977, social movement exhaustion and the election of a Democratic president gutted the counter-inaugural protest movement. In what the New York Times described as the most peaceful inauguration since 1965, a handful of peace and environmental groups maintained a quiet vigil, 150 Yippies rallied for marijuana legalization, and an imposing security apparatus maintained order. Even the election of Reagan failed to catalyze a powerful response; demonstrations against his 1981 inauguration included liberal feminist groups, a small anti-racist march organized by leftist parties, and a handful of the ever-present Yippies along with “other anarchistic splinter groups.” In response to bitterly cold weather, Reagan canceled the outdoor inaugural parade in 1985, leaving a few hundred anti-apartheid and Latin American solidarity marchers to shiver in the streets. One went to jail for spray-painting the FBI building while nineteen were arrested in a civil disobedience action at the South African embassy. Shortly after the inauguration, an anti-abortion march drew tens of thousands to the streets of Washington from across the country, indicating the strength of reactionary popular movements working in concert with the conservative administration.

For George H.W. Bush’s inauguration in 1989, security forces welded manhole covers shut and removed newspaper boxes and trash cans, but the kinds of disruptive protests that would have justified these measures failed to materialize. An anecdote circulates about a lone anarchist arrested while vehemently protesting Clinton’s inauguration in 1993—or was it 1997?—who received a one-way bus ticket back to his home in New Jersey for his troubles, courtesy of the DC police. The era of confrontational protests against presidential inaugurations seemed to have passed. While polite interest groups would still have space to hold their signs far from the procession of the powerful, perhaps the disruptive clashes of the Nixon years would join tie-dye and bell-bottoms as the stuff of ’60s nostalgia.

The Bush Era: Anti-Globalization, Anti-War, and Crowd-Surfing to Freedom

The anti-globalization movement changed all that. Amid the complacency of an economic boom and a Democratic administration, anarchism slowly but steadily re-emerged as a vibrant revolutionary force in the United States. Rooted in punk communities and anti-fascist networks, inspired by Zapatistas, pushed forward by the anti-consumerist and do-it-yourself ethos, anarchists around the country began to coalesce into combative anti-capitalist forces. Armed with the formidable new black bloc street tactic learned from European autonomous movements, which made its US debut in the late 1980s and early 1990s in Washington, DC, this new wave of anti-authoritarians formed coalitions with environmental, labor, feminist, and anti-militarist activists. New generations contested state and capitalist dominance of public space through Reclaim the Streets and Critical Mass, while activists from Earth First! and anti-sweatshop movements on college campuses showed the gains that could be made through direct action. Militant anarchist protest exploded into popular consciousness with the dramatic success of the November 1999 World Trade Organization (WTO) protests in Seattle. In addition to a comprehensive analysis that transcended single-issue politics, the new anarchists wielded confrontational and effective tactics that rejected “speaking truth to power” in favor of material disruption.

The modern era of counter-inaugural protest kicked off in 2001, fueled by a surging anti-globalization movement near the peak of its power. Fired up after large mobilizations in the preceding months against the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank in Washington, DC and the political party conventions in Los Angeles and Philadelphia, a wide range of activists set their sights on George W. Bush’s inauguration in January. After the controversial election outcome, many liberals waxed outrage over “hanging chads” and the supposed misdeeds of Florida’s election board and the role of the Supreme Court. Anarchists set a different tone from the beginning, however, having laid plans for demonstrations against whichever president won before knowing the outcome of the election. For weeks leading up to the protests, organizers framed their critiques of the “InaugurAuction,” highlighting how both candidates and parties answered to the dictates of capital above all else.

Between 20,000 and 50,000 protestors converged on DC for the inauguration, countered by some 7,000-10,000 law enforcement officers. For the first time, security forces initiated a system of checkpoints at entrances to the parade route. Although these limited the materials that Bush’s opponents could bring into the parade route, they also created bottlenecks that prevented some of his supporters from being able to reach their ticketed seats, as well as offering chokepoints for demonstrators to disrupt. Al Sharpton led a rally near the Capitol, while thousands more converged at Dupont Circle. Just nine arrests were officially reported, despite clashes at various points along the parade route and throughout the city. A lawsuit filed by protestors would later successfully contend that police had provoked and brutalized protestors and bystanders, forcing the department to revise its policies towards protests and pay out $685,000.

The initial call for a militant anarchist bloc came from the Barricada Collective, a project of the Boston chapter of the Northeast Federation of Anarcho-Communists (NEFAC). An invitation-only spokescouncil took place the night before, at which folks planned the march route and discussed tactics. A substantial black bloc converged on the morning of the inauguration, taking to the streets behind a banner reading, “Whoever They Vote For, We Are Ungovernable.” At one point, when the march had been hemmed in by riot police, an enterprising protestor used a wheelbarrow found at a nearby construction site as a wedge to lead a charge breaking out of the encirclement. The march managed to get quite close to the parade route before being beaten back. Bush, who had previously been traveling the route on foot and waving to onlookers, was forced to get back into his car, speeding in a motorcade past angry crowds to the White House like Richard Nixon in 1969. One protestor chucked an egg that smashed against the side of his limousine. By pushing militant resistance to the threshold of the inaugural parade, anarchists helped to set the tone for the next eight years, marking a turning point in the narrative of how people relate to the president.

After crashing the parade route, the black bloc made its way to the Navy Memorial. Insurgents climbed the flagpole, removed the symbols of patriotism and replaced them with a red and black flag. As infuriated police formed a barrier to close them in, the mischief-makers executed a dramatic escape, demonstrating once and for all the strategic value of experiences in punk subcultures. One jumped and scrambled away, while the other leapt from the flagpole onto the extended hands of the cheering marchers and crowd-surfed to freedom, bequeathing to future generations one of the most iconic images of anarchist resistance in the era. (Reactionaries, drawing on the moralistic strain of anti-globalization activism, were quick to complain that the flying anarchist sprang to freedom allegedly while sporting a pair of Nike shoes.)

In addition to the black bloc, another anarchist group created a pirate radio station in Washington, DC during the inauguration, jamming the airwaves with anti-electoral propaganda. Around the city, small flyers were distributed publicizing the FM frequency to thousands of listeners stuck in traffic snarled by the demonstrations. The station was carefully set up to allow for rapid disassembly as soon as police arrived to shut it down, which was successfully accomplished. In an era before livestreaming and instantaneous crowd-sourced reporting, expressing the “become the media” ethos by seizing the airwaves back from corporate stations seemed like a critical intervention. However, as one participant in the pirate radio project recalled, “We felt like bad-ass Adbusters-style culture jammers… but in retrospect, I wish I’d been in the black bloc.”

By the time of the next inauguration, the political context had shifted in dramatic ways. The Bush administration capitalized on the September 11th, 2001 attacks both to pursue profitable wars and occupations overseas and to crack down on domestic resistance under the new rubric of “homeland security.” Brutal repression hampered decentralized action against the FTAA in Miami in 2003, marking the beginning of a downturn in the “summit-hopping” model of mobile activist subcultures. Years of massive anti-war demonstrations failed to halt the US invasion of Iraq. This wave of protests had drawn huge numbers of people into the streets, but had been far more centrally controlled by non-profits and communist front groups than the decentralized rebellions of the anti-globalization movement. Anarchists took active roles in organizing a “Really Really Democratic Bazaar” at the 2004 Democratic National Convention in Boston and the DNC 2 RNC march, but a narrower focus on the Republican Party and the war in Iraq attracted more attention. Half a million people protested Bush at the Republican National Convention protests in New York City, driven by a broad coalition of moderates, liberals, and progressives whose “anybody but Bush” logic infected even some radicals. As a result, the overlapping movements converging against Bush’s second inauguration could still mobilize large numbers, but lacked the vitality and foundational respect for diversity of tactics of previous years.

Leading up to January 2005, anarchists from New York City issued a call for a mass anti-authoritarian march. On the morning of the inauguration, a black bloc assembled at a pre-announced convergence point and set off to confront the police lines along the parade route. Miscommunication led to the march departing before many of the anticipated people and materials had arrived, weakening the bloc’s force and prompting frustrating internal debates afterward. The march arrived at police lines a block from the inaugural route behind a reinforced banner that read, “Right Wing Scum, Your Time Has Come.” Unfortunately, the banner was only “reinforced” with flimsy PVC piping, lacking the spray insulation inside that increases its structural integrity. As a result, it quickly shattered when attacked by police, who broke up the banner and beat protesters with shards of PVC pipe.

Participants from that march regrouped at a reconvergence point and set out for the fence again. Encountering a truck stacked with wooden pallets, they chucked them into the street to build barricades against police vehicles and wielded them as shields at the front of march. As the heroic but doomed protestors charged an inaugural checkpoint, police drenched them with wave after wave of pepper spray from behind tall fences. Shortly after, the checkpoints leading into the parade were shut down by security. What role the black bloc’s charge played in their decision remains unknown.

Other statements had circulated among anarchists leading up to the inauguration calling for decentralized autonomous actions. A massive protest rally convened at Malcolm X Park and marched to McPherson Square. Elsewhere in the city, different crews of anarchists created minor disruptions and linked with other protests and marches. Later that night, a packed punk show in a church basement featured speeches from stage and tables of anarchist literature. Afterwards, masked accomplices distributed bandannas, gloves, and cans of spray paint to the enthusiastic concertgoers, some two hundred of whom set off into the streets. The march surged through the Adams Morgan neighborhood, smashing banks and corporate businesses and attacking a police substation with projectiles. A massive banner was dropped over a Starbucks reading, “From DC to Iraq: With Occupation Comes Resistance.” Police eventually detained and arrested dozens of people, including many teenagers participating in a demonstration for the first time, forcing them to kneel in snow in the street for hours. Ultimately none of the charges stuck, and some indignant arrestees successfully sued the police department again and reaped financial rewards for their participation.

Some radicals raised a stink about the march, complaining that the smashed police station included a Latino/a community liaison unit, and initiating a witch-hunt at the 2005 National Conference on Organized Resistance later that winter about who was responsible for the “violence.” Beyond constructive internal debates over strategy and tactics, the controversy over the march revealed the fracturing consensus over diversity of tactics and tensions around responses to white supremacy that would rear their head four years later.

The Obama Era: “Hope From People” and Missed Opportunities

As the anti-war movement waned and protest activity lulled in 2006-2007, the “anybody but Bush” coalition turned their sights to the next presidential election. The Obama campaign successfully appropriated most of the energy that had been directed into grassroots social movements previously, leaving anarchists largely alone in dissenting from the rhetoric of electoral “hope and change.” However, as the Obama campaign crested, the emerging economic crisis prompted a new wave of resistance, as anarchists roused themselves to organize anti-capitalist marches and participate in eviction defenses. Using a model of decentralized, coordinated consultas to build momentum around the country, anti-authoritarians mobilized extensively to protest both the Democratic and Republican conventions in 2008 through the Unconventional Action network, which persisted in some areas as a foundation for future resistance. With Obama triumphant, how would anarchists respond to the inauguration?

Unfortunately, anarchists collectively failed to take a strong stand by undertaking visible and confrontational protest at the inauguration. In the weeks after Obama’s victory, considerable debate erupted over whether or how to protest. Would a protest by a (majority white) group of anarchists against the first Black president be perceived as a slap in the face to Black communities? Or even be mistaken for white supremacists, who were rumored to be planning protests as well? While some constructive conversations about strategy, messaging, and white supremacy did take place, it became clear that many anarchists would forego counter-inaugural activity altogether.

One effort to salvage some anarchist presence amidst the ambivalence led to a dismaying statement of anarchist liberalism and compromise. Cindy Milstein and other anarchists authored a call titled “Hope From People,” calling for an unmasked “presence rather than protest” in the form of a “Celebrate People’s History and Popular Power Bloc.” This convergence was intended to form links with the “true rainbow coalition” of pro-Obama attendees by artistically celebrating forms of popular resistance. Contrasting “breaking things” with serious movement building and meaningful anti-racist work, the “Hope From People” call acknowledged that although anarchists oppose all presidents, “not all heads of state are alike, and if we fail to recognize both the historical meaning and power of this particular moment, we will ensure our own irrelevance.” That barely a dozen anarchists turned out to distribute flyers to the jubilant crowd reflected the true irrelevance of this approach. Yet the call attracted the signatures of dozens of prominent anarchists and radicals from Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn to groups such as Unconventional Denver and Wooden Shoe Books. By diverting experienced organizers into an equivocal non-event, the “Hope From People” mishap splintered any chance of concerted anarchist resistance to Obama’s inauguration.

Not all anarchists succumbed to this diversion. A CrimethInc. analysis noted that “some, afraid of being misunderstood, caution against confrontational organizing of any kind, forfeiting the initiative precisely when it is most important to maintain radical momentum.” (Not to say we told you so, but…) Another statement called for disruptions of capitalist and corporate targets during the inauguration, though few heeded it. Perhaps more importantly, the outbreak of the Oscar Grant riots in Oakland and the student occupations at the New School in New York drew many anarchists into immediate confrontational struggles far from Washington in the weeks before the inauguration. While a number of anarchists arrived in the capitol intent on disruptive action, fierce internal debates foreclosed any possibility of concerted public protest. When the “Hope From People” project, as predicted, came to nothing, many disillusioned radicals turned their attention away from the presidency to other targets.

While anarchists remained active in a variety of struggles, 2009 marked a new low point for counter-inaugural activity. In an effort to avoid alienating potential allies, many lost sight of the basic principles of anarchism—opposition to the state, capitalism, and all forms of hierarchy, regardless of what figurehead stands at the helm. Worse, anarchists missed a critical opportunity to define the meaning of opposition to Obama. In the absence of visible anti-authoritarian resistance, right-wingers and racists stepped into the void uncontested and cornered the market on anti-government sentiment, facilitating the rise of the Tea Party movement and other reactionary formations. The residue of the “anybody but Bush” logic and the desire to see Obama’s election as a symbolic victory against oppression actually bolstered the smooth functioning of US militarism, the prison industrial complex, and anti-immigrant repression, all of which accelerated under the new administration with far less scrutiny or resistance than Bush’s initiatives faced. Meanwhile, within anarchist circles, unresolved conflicts over how to counter white supremacy sharpened, revealing tensions around race, identity, and solidarity that would repeatedly resurface in the years to come.

In 2013, some anarchists approached the inauguration determined not to repeat the mistakes of four years before. Although the unexpected surge of the Occupy movement of 2011-2012 had largely receded, it left in its wake many newly politicized activists uninfected by the equivocations of the “anybody but Bush” era. To these younger radicals, the Obama administration meant mass surveillance, drone strikes, evictions, and deportations, not a symbol of hope and change for marginalized peoples. Still, in stark contrast to the Bush era, the largest demonstrations tended to number in the hundreds rather than the tens of thousands, and a mass convergence with the audacity to charge the inaugural parade route would have been unthinkable.

Local anarchists organized a counter-inaugural weekend of workshops, discussions, and cultural events, including debates that reflected how anarchist analysis had developed beyond the limits of the previous years. On the day of the inauguration, an anarchist march behind a banner reading “Without Government We Can Move Forward” marched through the Dupont Circle neighborhood. The night before, a feisty black bloc took to the streets of Chinatown, smashing the windows of banks, ATMs, and a Hooters restaurant before dispersing without arrests. At the night march, an older guard of black bloc anarchists struggled to find common cause with a newer generation of Occupy radicals who, for example, understood livestreaming as a form of radically democratic transparency rather than harmful crowd-sourced surveillance. While these marches numbered only in the dozens, they maintained the continuity of anti-authoritarian resistance to the inaugural spectacle despite the desertion of liberals and progressives.

Conclusion: Lessons Learned for the Trump Era and Beyond

Now as 2017 approaches, the wheel has turned again. The counter-inaugural demonstrations against Trump are likely to be the largest in many years, perhaps ever. And once again, anarchists confront advantages and disadvantages: massive numbers in the streets and broad popular support, but a focus on Trump as an individual rather than democracy and the state as a whole, as well as efforts to contain and control rebellious protest. While the last two years have seen an explosion of large, angry, disruptive street protests, they have also seen a proliferation of policing tactics, both internal and external to these movements. While few will dispute that we should be in the streets, many will attempt to redirect our anger and constrict our possibilities – and the stakes are higher than ever.

From past cycles of demonstrations, we’ve learned that we can exercise a surprising capacity for disruption – but attempting to do the same thing twice rarely succeeds. The DC police department operates under considerable restrictions due to frequent lawsuits attacking their repression of protest, so marchers may have more latitude than in other cities. However, the concentration of police, military, and private security will be prodigious, and the explosion of surveillance technology inside and outside of popular movements increases our risks after the fact. We will also likely have to confront the presence of armed white supremacists and fascists emboldened by Trump’s election, potentially a serious escalation from the shouting matches with Bush supporters in previous years. Popular sympathy for Black Lives Matter has at least opened conversation in broader circles about the legitimacy of rioting and disruption. Yet no consensus around diversity of tactics exists between distinct social movements, and the discourse of nonviolence has received a boost – however misguided – from heroic resistance at Standing Rock and misreadings of revolts overseas. These contradictory realities mean that possibilities as well as risks are extraordinarily heightened in this new terrain.

Above all, when we resist Trump and all politicians on January 20, whether in DC or in our own communities, we’re not just fighting to shut down business as usual. We’re fighting to define what it will mean to be against Trump in the years to come. Will our energy be diverted into rallying support for Democrats or raising money for nonprofits? Or will we build towards a world beyond all parties and politicians? Can our opposition to Trump transcend single issues and undermine the legitimacy of capitalism and the state altogether?

On January 20, we will take to the streets. But what we do in the months and years beyond the inauguration will determine the nature of resistance the world that made Trump possible.

References and Links

For more information about the anarchist counter-inaugural actions discussed above, check out these resources:

- “Not My President,” an Indymedia documentary about the 2001 inauguration protests (including the infamous “stage dive to freedom”).

- The DC Police Department’s Settlement with protestors after the 2001 counter-inaugural demonstrations.

- “Demonstrating Resistance: Mass Action and Autonomous Action in the Election Year,” including an in-depth report on the 2005 counter-inaugural protests, originally published in Rolling Thunder #1.

- “Communique from Bush Inauguration,” a short Indymedia documentary about the anti-authoritarian bloc at the 2005 inauguration.

- “Stay the Course,” a CrimethInc. analysis from late 2008 anticipating directions for resistance in the Obama era. -“Hope From People,” the text of the infamous call for a “Celebrate People’s History and Popular Power Bloc” at the 2009 inauguration.

- For the 2013 inauguration, see the brief mainstream article on the black bloc march and photo of the Dupont Circle anarchist march

- And most importantly, to prepare for the 2017 counter-inaugural demonstrations, see the “No Peaceful Transition” call for militant anarchist action against Trump, and the Disrupt J20 page from the DC Counter-Inaugural Welcoming Committee.